- Home

- Dean Koontz

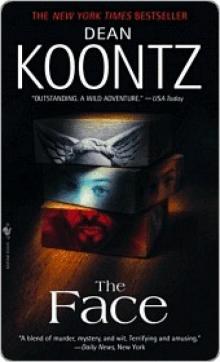

The Face

The Face Read online

Contents

COVER PAGE

TITLE PAGE

DEDICATION

EPIGRAPH

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

CHAPTER 40

CHAPTER 41

CHAPTER 42

CHAPTER 43

CHAPTER 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

CHAPTER 47

CHAPTER 48

CHAPTER 49

CHAPTER 50

CHAPTER 51

CHAPTER 52

CHAPTER 53

CHAPTER 54

CHAPTER 55

CHAPTER 56

CHAPTER 57

CHAPTER 58

CHAPTER 59

CHAPTER 60

CHAPTER 61

CHAPTER 62

CHAPTER 63

CHAPTER 64

CHAPTER 65

CHAPTER 66

CHAPTER 67

CHAPTER 68

CHAPTER 69

CHAPTER 70

CHAPTER 71

CHAPTER 72

CHAPTER 73

CHAPTER 74

CHAPTER 75

CHAPTER 76

CHAPTER 77

CHAPTER 78

CHAPTER 79

CHAPTER 80

CHAPTER 81

CHAPTER 82

CHAPTER 83

CHAPTER 84

CHAPTER 85

CHAPTER 86

CHAPTER 87

CHAPTER 88

CHAPTER 89

CHAPTER 90

CHAPTER 91

CHAPTER 92

CHAPTER 93

CHAPTER 94

CHAPTER 95

CHAPTER 96

NOTE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ALSO BY DEAN KOONTZ

AVAILABLE NOW

COPYRIGHT

This book is dedicated to three exceptional men—and to their wives, who have worked so very hard to sculpt them from such rough clay. From the ground up: To Leason and Marlene Pomeroy, to Mike and Edie Martin, and to Jose and Rachel Perez. After The Project, I will not be able to get up in the morning, spend a moment at home during the day, or go to bed at night without thinking of you. I guess I’ll just have to live with that.

The civilized human spirit…cannot get rid of a feeling of the uncanny.

—Doctor Faustus, THOMAS MANN

CHAPTER 1

AFTER THE APPLE HAD BEEN CUT IN HALF, THE halves had been sewn together with coarse black thread.

Ten bold stitches were uniformly spaced. Each knot had been tied with a surgeon’s precision.

The variety of apple, a red delicious, might have significance. Considering that these messages had been delivered in the form of objects and images, never in words, every detail might refine the sender’s meaning, as adjectives and punctuation refined prose.

More likely, however, this apple had been selected because it wasn’t ripe. Softer flesh would have crumbled even if the needle had been used with care and if each stitch had been gently cinched.

Awaiting further examination, the apple stood on the desk in Ethan Truman’s study. The black box in which the apple had been packed also stood on the desk, bristling with shredded black tissue paper. The box had already yielded what clues it contained: none.

Here in the west wing of the mansion, Ethan’s ground-floor apartment was comprised of this study, a bedroom, a bathroom, and a kitchen. Tall French windows provided a clear view of nothing real.

The previous occupant would have called the study a living room and would have furnished the space accordingly. Ethan did too little living to devote an entire room to it.

With a digital camera, he had photographed the black box before opening it. He had also taken shots of the red delicious from three angles.

He assumed that the apple had been sliced open in order to allow for the insertion of an object into the core. He was reluctant to snip the stitches and to take a look at what might lie within.

Years as a homicide detective had hardened him in some respects. In other ways, too much experience of extreme violence had made him vulnerable.

He was only thirty-seven, but his police career was over. His instincts remained sharp, however, and his darkest expectations were undiminished.

A sough of wind insisted at the French panes. A soft tapping of blown rain.

The languid storm gave him excuse enough to leave the apple waiting and to step to the nearest window.

Frames, jambs, rails, muntins—every feature of every window in the great house had been crafted in bronze. Exposure to the elements promoted a handsome mottled-green patina on exterior surfaces. Inside, diligent maintenance kept the bronze a dark ruby-brown.

The glass in each pane was beveled at every edge. Even in the humblest of service rooms—the scullery, the ground-floor laundry—beveling had been specified.

Although the residence had been built for a film mogul during the last years of the Great Depression, no evidence of a construction budget could be seen anywhere from the entrance foyer to the farthest corner of the last back hall.

When steel sagged, when clothes grew moth-eaten on haberdashery racks, when cars rusted on showroom floors for want of customers, the film industry nevertheless flourished. In bad times as in good, the only two absolute necessities were food and illusions.

From the tall study windows, the view appeared to be a painting of the kind employed in motion-picture matte shots: an exquisitely rendered dimensional scene that, through the deceiving eye of the camera, could serve convincingly as a landscape on an alien planet or as a place on this world perfected as reality never allowed.

Greener than Eden’s fields, acres of lawn rolled away from the house, without one weed or blade of blight. The majestic crowns of immense California live oaks and the drooping boughs of melancholy deodar cedars, each a classic specimen, were silvered and diamonded by the December drizzle.

Through skeins of rain as fine as angel hair, Ethan could see, in the distance, the final curve of the driveway. The gray-green quartzite cobblestones, polished to a sterling standard by the rain, led to the ornamental bronze gate in the estate wall.

During the night, the unwanted visitor had approached the gate on foot. Perhaps suspecting that this barrier had been retrofitted with modern security equipment and that the weight of a climber would trigger an alarm in a monitoring station, he’d slung the package over the high scrolled crest of the gate, onto the driveway.

The box containing the apple had been cushioned by bubble wrap and then sealed in a white plastic bag to protect it further from foul weather. A red gift bow, stapled to the bag, ensured that the contents would not be mistaken for garbage.

Dave Ladman, one of two guards on the graveyard shift, retrieved the delivery at 3:56 A.M. Handling

the bag with care, he had carried it to the security office in the groundskeeper’s building at the back of the estate.

Dave and his shift partner, Tom Mack, x-rayed the package with a fluoroscope. They were looking for wires and other metal components of an explosive device or a spring-loaded killing machine.

These days, some bombs could be constructed with no metal parts. Consequently, following fluoroscopy, Dave and Tom employed a trace-scent analyzer capable of recognizing thirty-two explosive compounds from as few as three signature molecules per cubic centimeter of air.

When the package proved clean, the guards unwrapped it. Upon discovering the black gift box, they had left a message on Ethan’s voice mail and had set the delivery aside for his attention.

At 8:35 this morning, one of the two guards on the early shift, Benny Nguyen, had brought the box to Ethan’s apartment in the main house. Benny also arrived with a videocassette containing pertinent segments of tape from perimeter cameras that captured the delivery.

In addition, he offered a traditional Vietnamese clay cooking pot full of his mother’s com toy cam, a chicken-and-rice dish of which Ethan was fond.

“Mom’s been reading candle drippings again,” Benny said. “She lit a candle in your name, read it, says you need to be fortified.”

“For what? The most strenuous thing I do these days is get up in the morning.”

“She didn’t say for what. But not just for Christmas shopping. She had that temple-dragon look when she talked about it.”

“The one that makes pit bulls bare their bellies?”

“That one. She said you need to eat well, say prayers without fail each morning and night, and avoid drinking strong spirits.”

“One problem. Drinking strong spirits is how I pray.”

“I’ll just tell Mom you poured your whiskey down the drain, and when I left, you were on your knees thanking God for making chickens so she could cook com tay cam.”

“Never knew your mom to take no for an answer,” Ethan said.

Benny smiled. “She won’t take yes for an answer, either. She doesn’t expect an answer at all. Only dutiful obedience.”

Now, an hour later, Ethan stood at a window, gazing at the thin rain, like threads of seed pearls, accessorizing the hills of Bel Air.

Watching weather clarified his thinking.

Sometimes only nature felt real, while all human monuments and actions seemed to be the settings and the plots of dreams.

From his uniform days through his plainclothes career, friends on the force had said that he did too much thinking. Some of them were dead.

The apple had come in the sixth black box received in ten days. The contents of the previous five had been disturbing.

Courses in criminal psychology, combined with years of street experience, made Ethan hard to impress in matters regarding the human capacity for evil. Yet these gifts provoked his deep concern.

In recent years, influenced by the operatically flamboyant villains in films, every common gangbanger and every would-be serial killer, starring in his own mind movie, could not simply do his dirty work and move along. Most seemed to be obsessed with developing a dramatic persona, colorful crime-scene signatures, and ingenious taunts either to torment their victims beforehand or, after a murder, to scoff at the claimed competence of law-enforcement agencies.

Their sources of inspiration, however, were all hackneyed. They succeeded only in making fearsome acts of cruelty seem as tiresome as the antics of an unfunny clown.

The sender of the black boxes succeeded where others failed. For one thing, his wordless threats were inventive.

When his intentions were at last known and the threats could be better understood in light of whatever actions he took, they might also prove to be clever. Even fiendishly so.

In addition, he conferred on himself no silly or clumsy name to delight the tabloid press when eventually they became aware of his game. He signed no name at all, which indicated self-assurance and no desperate desire for celebrity.

For another thing, his target was the biggest movie star in the world, perhaps the most guarded man in the nation after the President of the United States. Yet instead of stalking in secret, he revealed his intentions in wordless riddles full of menace, ensuring that his quarry would be made even more difficult to reach than usual.

Having turned the apple over and over in his mind, examining the details of its packaging and presentation, Ethan fetched a pair of cuticle scissors from the bathroom. At last he returned to the desk.

He pulled the chair from the knee space. He sat, pushed aside the empty gift box, and placed the repaired apple at the center of the blotter.

The first five black boxes, each a different size, and their contents had been examined for fingerprints. He had dusted three of the deliveries himself, without success.

Because the black boxes came without a word of explanation, the authorities would not consider them to be death threats. As long as the sender’s intention remained open to debate, this failed to be a matter for the police.

Deliveries 4 and 5 had been trusted to an old friend in the print lab of the Scientific Investigation Division of the Los Angeles Police Department, who processed them off the record. They were placed in a glass tank and subjected to a cloud of cyanoacrylate fumes, which readily condensed as a resin on the oils that formed latent prints.

In fluorescent light, no friction-ridge patterns of white resin had been visible. Likewise, in a darkened lab, with a cone-shaded halogen lamp focused at oblique angles, the boxes and their contents continued to appear clean.

Black magnetic powder, applied with a Magna-Brush, had revealed nothing. Even bathed in a methanol solution of rhodamine 6G, scanned in a dark lab with the eerie beam from a water-cooled argon ion laser generator, the objects had revealed no telltale luminous whorls.

The nameless stalker was too careful to leave such evidence.

Nevertheless, Ethan handled this sixth delivery with the care he’d exhibited while examining the five previous items. Surely no prints existed to be spoiled, but he might want to check later.

With the cuticle scissors, he snipped seven stitches, leaving the final three to serve as hinges.

The sender must have treated the apple with lemon juice or with another common culinary preservative to ensure a proper presentation. The meat was mostly white, with only minor browning near the peel.

The core remained. The seed pocket had been scooped clean of pits, however, to provide a setting for the inserted item.

Ethan had expected a worm: earthworm, corn earworm, cutworm, leech, caterpillar, trematode, one type of worm or another.

Instead, nestled in the apple flesh, he found an eye.

For an ugly instant, he thought the eye might be real. Then he saw that it was only a plastic orb with convincing details.

Not an orb, actually, but a hemisphere. The back of the eye proved to be flat, with a button loop.

Somewhere a half-blinded doll still smiled.

When the stalker looked at the doll, perhaps he saw the famous object of his obsession likewise mutilated.

Ethan was nearly as disturbed by this discovery as he might have been if he’d found a real eye in the red delicious.

Under the eye, in the hollowed-out seed pocket, was a tightly folded slip of paper, slightly damp with absorbed juice. When he unfolded it, he saw typing, the first direct message in the six packages:

THE EYE IN THE APPLE? THE WATCHFUL WORM? THE WORM OF ORIGINAL SIN? DO WORDS HAVE ANY PURPOSE OTHER THAN CONFUSION?

Ethan was confused, all right. Whatever it meant, this threat—the eye in the apple—struck him as particularly vicious. Here the sender had made an angry if enigmatic statement, the symbolism of which must be correctly interpreted, and urgently.

CHAPTER 2

BEYOND THE BEVELED GLASS, THE IRON-BLACK clouds that had masked the sky now hid themselves behind gray veils of trailing mist. The wind went elsewhere with its lamentations,

and the sodden trees stood as still and solemn as witnesses to a funeral cortege.

The gray day drifted into the eye of the storm, and from each of his three study windows, Ethan observed the mourning weather while meditating on the meaning of the apple in the context of the five bizarre items that had preceded it. Nature peered back at him through a milky cataract and, in sympathy with his inner vision, remained clouded.

He supposed the shiny apple might represent fame and wealth, the enviable life of his employer. Then the doll’s eye might be a worm of sorts, a symbol of a particular corruption at the core of fame, and therefore an accusation, indictment, and condemnation of the Face.

For twelve years, the actor had been the biggest box-office draw in the world. Since his first hit, the celebrity-mad media referred to him as the Face.

This flattering sobriquet supposedly had arisen simultaneously from the pens of numerous entertainment reporters in a shared swoon of admiration for his charismatic good looks. In truth, no doubt a clever and perpetually sleepless publicist had called in favors and paid out cold cash to engineer this spontaneous acclamation and then to sustain it for more than a decade.

In a black-and-white Hollywood so distant in time and quality that contemporary moviegoers had only a little more knowledge of it than they had of the Spanish-American War, a fine actress named Greta Garbo had in her day been known as the Face. That flattery had been the work of a studio flack, but Garbo had proved to be more than mere flackery.

For ten months, Ethan had been chief of security for Channing Manheim, the Face of the new millennium. As yet he hadn’t glimpsed even the suggestion of Garboesque depths. The face of the Face seemed to be nearly all there was of Channing.

Ethan didn’t despise the actor. The Face was affable, as relaxed as might be a genuine demigod living with the sureness that life and youth were for him eternal.

The star’s indifference to any circumstances other than his own arose neither from self-absorption nor from a willful lack of compassion. Intellectual limitations denied him an awareness that other people had more than a single script page of backstory, and that their character arcs were too complex to be portrayed in ninety-eight minutes.

His occasional cruelties were never conscious.

If he hadn’t been who he was, however, and if he hadn’t been so striking in appearance, nothing that Channing said or did would have left an impression. In a Hollywood deli that named sandwiches after stars, Clark Gable might have been roast beef and Liederkranz on rye with horseradish; Cary Grant might have been peppered chicken breast with Swiss cheese on whole wheat with mustard; and Channing Manheim would have been watercress on lightly buttered toast.

Breathless

Breathless Lightning

Lightning The Taking

The Taking The Door to December

The Door to December Odd Thomas

Odd Thomas Midnight

Midnight Whispers

Whispers Odd Interlude #2

Odd Interlude #2 The Mask

The Mask Watchers

Watchers By the Light of the Moon

By the Light of the Moon Night Chills

Night Chills Brother Odd

Brother Odd False Memory

False Memory The Darkest Evening of the Year

The Darkest Evening of the Year Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy The Good Guy

The Good Guy Hideaway

Hideaway Innocence

Innocence Your Heart Belongs to Me

Your Heart Belongs to Me Forever Odd

Forever Odd Intensity

Intensity Saint Odd

Saint Odd Dragon Tears

Dragon Tears The Husband

The Husband Final Hour

Final Hour Demon Seed

Demon Seed City of Night

City of Night From the Corner of His Eye

From the Corner of His Eye A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog

A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog Seize the Night

Seize the Night Winter Moon

Winter Moon Strange Highways

Strange Highways The Silent Corner

The Silent Corner Twilight Eyes

Twilight Eyes Velocity

Velocity The Bad Place

The Bad Place Cold Fire

Cold Fire The Whispering Room

The Whispering Room Ricochet Joe

Ricochet Joe The Crooked Staircase

The Crooked Staircase Tick Tock

Tick Tock The Face

The Face Sole Survivor

Sole Survivor Strangers

Strangers Deeply Odd

Deeply Odd Odd Interlude #3

Odd Interlude #3 The Vision

The Vision Phantoms

Phantoms Prodigal Son

Prodigal Son Odd Hours

Odd Hours Last Light

Last Light Fear Nothing

Fear Nothing Odd Interlude #1

Odd Interlude #1 One Door Away From Heaven

One Door Away From Heaven Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder

Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder The City

The City The Dead Town

The Dead Town The Voice of the Night

The Voice of the Night Dark Rivers of the Heart

Dark Rivers of the Heart The Key to Midnight

The Key to Midnight Lost Souls

Lost Souls Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever

Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever Odd Apocalypse

Odd Apocalypse Icebound

Icebound The Book of Counted Sorrows

The Book of Counted Sorrows The Neighbor

The Neighbor Ashley Bell

Ashley Bell Santa's Twin

Santa's Twin Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive The Eyes of Darkness

The Eyes of Darkness The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle Writing Popular Fiction

Writing Popular Fiction City of Night f-2

City of Night f-2 Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle What the Night Knows: A Novel

What the Night Knows: A Novel Demon Child

Demon Child Starblood

Starblood Surrounded mt-2

Surrounded mt-2 Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story) Odd Interlude

Odd Interlude The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle The City: A Novel

The City: A Novel Deeply Odd ot-7

Deeply Odd ot-7 Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story) The House of Thunder

The House of Thunder Odd Interlude ot-5

Odd Interlude ot-5 Fear That Man

Fear That Man Odd Is on Our Side

Odd Is on Our Side Relentless

Relentless A Big Little Life

A Big Little Life Hanging On

Hanging On The Forbidden Door

The Forbidden Door Dragonfly

Dragonfly The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense Final Hour (Novella)

Final Hour (Novella) The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours Odd Interlude (Complete)

Odd Interlude (Complete) The Funhouse

The Funhouse 77 Shadow Street

77 Shadow Street What the Night Knows

What the Night Knows Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel

Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel The Servants of Twilight

The Servants of Twilight Star quest

Star quest Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel

Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel Chase

Chase Eyes of Darkness

Eyes of Darkness The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single)

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single) Sussurri

Sussurri The Moonlit Mind (Novella)

The Moonlit Mind (Novella) Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel

Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel![Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/ricochet_joe_kindle_in_motion_kindle_single_preview.jpg) Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single)

Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Innocence: A Novel

Innocence: A Novel Beastchild

Beastchild A Darkness in My Soul

A Darkness in My Soul Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages

Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle

The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle Frankenstein - City of Night

Frankenstein - City of Night Shadowfires

Shadowfires Last Light (Novella)

Last Light (Novella) Frankenstein - Prodigal Son

Frankenstein - Prodigal Son Ticktock

Ticktock Dance with the Devil

Dance with the Devil You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story)

You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story) The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Darkness Under the Sun

Darkness Under the Sun Dark Of The Woods

Dark Of The Woods Dean Koontz's Frankenstein

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein Frankenstein

Frankenstein The Face of Fear

The Face of Fear Children of the Storm

Children of the Storm Mr. Murder

Mr. Murder