- Home

- Dean Koontz

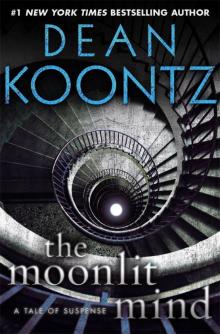

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Page 10

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Read online

Page 10

One street becomes another, another, another. Alleyways entice, and in one of them a man who smells of stale sweat and whiskey grabs him—“Whoa there, Huck Finn, you got something for me?”—but Crispin wrenches free.

He runs, runs until his chest aches, until his throat is raw from breathing through his mouth. When at last he halts, he is standing on the sidewalk at an entrance to St. Mary Salome Cemetery.

Although he does not remember dropping it, the book with Saint Michael on the cover is gone. He has no recollection of digging the rumpled bills from his pocket, either, but clutched in his right hand are the two fives and the single that he took from the petty-cash envelope on the butler’s desk.

So much of such devastating import has happened in the past hour that Crispin shouldn’t be able to unravel a complex thought from his mental and emotional mare’s nest. But as he regards the money in his hand, he realizes that the moment he took it, he knew that he would not die to save his brother, that in the end he would cut and run. This was his getaway money, a pathetic little stash to tide him over during his first day or two on the streets. He could have taken the entire sixty-one dollars, but he would have known right then that he had no intention of heroic action. He prided himself on taking only eleven, on not being a thief, to distract himself from the truth of his cowardice. He went into the basement not to find and save his little brother, not really, but instead because the secret of the room behind the steel door was alluring, as alluring as the luxury of Theron Hall, as tempting as a life of leisure, as seductive as Nanny Sayo.

He begins to weep and then to sob uncontrollably for Mirabell and for Harley, but also for himself, for what is lost as much as for who is lost. He tries to throw down the money, but his hand has intentions of its own, cramming the bills into his pocket once more. He cannot run from the money because it is part of him now, and he can’t run from himself, no one can, but he tries.

He races into the cemetery, weaving among the headstones, which in the moonlight appear to be carved of ice. He wishes this were as simple as a creepy comic book, wishes someone long buried would erupt from the ground, judge him with a few harsh words, seize him, pull him down, and bring him to his end. But the dead want nothing to do with him, they will not rise for him, neither will they speak.

At last, at the center of the cemetery, having passed through the arrangement of mausoleum walls where ashes rather than bodies are interred, in the center of the circular lawn, he clambers onto the circular mass of granite that serves as a bench, and lies on his back.

No slightest susurration of the city reaches here. His labored breathing and his sobbing are the only sounds. He cries himself to silence among these memorials to lost souls.

He thinks that he will never sleep again, that he is too wicked to deserve sleep. He lies on his back, staring at the moon, and the cratered face of the old man in the moon seems to stare back at him. The night sky grows deeper. The earlier stars call forth others. He sleeps.

17

Hard years of change, now Crispin thirteen, no longer quite a boy, not yet a man …

Good dog Harley sits on the booth bench beside Amity Onawa, as if the part of the story that the girl likes best is also the most appealing part to him. His eyes twinkle in the candlelight.

“Harley takes his paw off the empty box,” Crispin continues, “and I put the cards away. I’m able to get back to sleep for a while, with no bad dreams. In the morning, I expect to go upstairs to the magic-and-game shop before the start of the business day. I should be able to unlock the front door from inside, and if I can’t, me and Harley will wait until the old man and woman open the place, then we’ll dash out past them, no explanations.”

“Sounds easy,” Amity says, and smiles again.

“Totally easy. Except when we go upstairs from the basement storeroom, there isn’t any magic shop like there was the night before. The store is empty, bare, no business there of any kind.”

“No old man with green eyes and six emerald rings.”

“No one, nothing,” Crispin confirms. “Hasn’t been anything happening there for a long time, judging by the dust and cobwebs.”

“But the storeroom …”

“I go back down the stairs. Harley doesn’t bother coming with me, as if he already knows what I’ll find. Which is nothing. All the shelves and all the stock on them are gone. The storeroom is as empty as the store above it.”

“This is two days after you ran away from Theron Hall.”

“Two days but the third night. After everything that happened in Theron Hall, maybe I should have been scared half to death by the magic shop disappearing, but I wasn’t.”

She stares at him unblinking. He does not look away from her, because this is the hardest part for him to tell, and it means more if he can tell it eye to eye.

“I was able to unlock the door from inside, and we closed it behind us as we went. The day was warm for early October, the sky so blue, and birds singing in the streetside trees. I looked back at the shop and saw a FOR RENT sign taped to the inside of the door glass. At the bottom was a phone number and a Realtor’s contact name. The name was Miss Regina Angelorum. I was too young then to know that it was a name but also more than a name. Years would pass before I knew what it meant, but right then, at the start of my third day free of Theron Hall, I was certain that in spite of my many weaknesses, in spite of my cowardice and my failure to save Mirabell or Harley, I was meant to live, to grow and change, and to accomplish something in this world that mattered.”

They are silent together in the candlelight.

Amity’s eyes are worlds of mystery, as Crispin imagines his eyes must be to her.

Four candles in red-glass cups brighten the table. But for what comes next, Amity wants more light. Earlier she gathered four more candles for this moment. With a butane match, she sets the wicks afire.

Crispin opened the box of cards earlier. Now he shuffles three times, hesitates, then shuffles thrice again.

Amity wants him to deal, and yet she doesn’t. She reaches toward him with one hand, as if to stop him, but then crosses her arms on her chest once more and hugs herself.

With no false drama, dealing them quickly, Crispin turns up four sixes. They are clean cards when they leave his hand, but as he turns them over, they are dirty, creased, and moldy.

The time has come for him to return to Theron Hall.

18

Having dealt the four sixes on Sunday evening, he must wait until the first employees arrive on Monday to avoid triggering the perimeter alarm. Following a route described by Amity, boy and dog slip out of the department store without being seen by any of the early-arriving guards and maintenance people.

They have no reason to wait for nightfall before approaching Theron Hall. There is no safety in darkness and perhaps more risk.

The first snow of the season fell Saturday night through Sunday morning. Already another storm has moved in. As Crispin and Harley set out for Shadow Hill, Shadow Street, and the house at the crest, new snow begins to sift down upon the old.

Winter transforms the city, white petals floating through an almost windless day, and everywhere the mantles and plowed mounds of the weekend storm remain largely pristine, not yet badly soiled by a workday. How easy it might be to think that with the casting down of this crystal manna, the great metropolis has been sanctified, that it is as innocent as these bridal veils make it seem. Easy for others, perhaps, but not for Crispin.

They approach the grand house from the back street, which is too wide and—when the pavement is visible—too ornately cobbled to be called a mere alley.

A stately carriage house, which serves as a garage, stands at the rear of the property. The pathway that leads from garage to house hasn’t been shoveled, and no footprints disturb the coverlet of snow.

According to what Amity overheard when she served Clarette and friends tea in Eleanor’s a couple of weeks earlier, the family—if such a word applies—and most of

the staff are by now in Brazil.

The few who remain have evidently kept busy inside rather than venture into the cold.

Crossing the exposed ground between garage and house, Crispin searches the three floors of windows. No pale face appears at any pane.

A part of him believes that the power that has saved him often in the past few years, the power that wants him to return to Theron Hall to conclude unfinished business, has armored him against harm and will lead him to the third floor and safely away again without a violent encounter. But another part of him, a less wishful Crispin and one who knows that journeying through the fields of evil is the price we pay for free will, expects the worst.

If they know that he stole one of the spare house keys on that September night, they might have changed the lock. Or they might leave it unchanged in anticipation of his return.

Of the three back doors, he chooses the one that opens into the mud room behind the kitchen. The key works. He eases the door open.

The space is dark but for the snow light that presses coldly through two small windows.

He stands listening to a house so silent that perhaps everyone went to Rio, leaving only ghosts behind.

Because he doesn’t want to take off his backpack to use a chair, Crispin leans against the cabinetry to use the mud room’s small whisk broom to brush the caked snow from his shoes and from the legs of his jeans.

The dog shakes his thick coat, flinging off melted snow and bits of icy slush. That noisy moment of grooming doesn’t raise an alarm, which must mean that no one on the skeleton staff is nearby.

Aware that they will for a while leave wet footprints, Crispin is nevertheless disposed to move at once rather than dry his shoes and the dog’s paws with rags.

The kitchen is as shadowy and deserted as the mud room. The only sound is the hum of the refrigerators.

If three or even four of the staff have stayed behind to keep the house clean and functional, they are spread over such a vastness of rooms that he is unlikely to come face-to-face with one of them. He must also remember that, whatever else they may be, they are not demons. They are still human beings, as vulnerable as he is, as prone to error.

The boy decides to let the dog lead, and Harley takes him to the south stairs. Within the open tube of stone, the bronze railing and the spiral treads wind upward like the twisted spine of some bizarre Jurassic beast.

At the top, he leans over the railing and looks down, to be sure that no one is ascending quietly behind them. At the bottom of the stairwell, a full moon shines, as though Crispin is gazing up through a roofless tower instead of down. He assumes that whether this is a trick of light or something more, it is in either case a sign, and not a bad one, because the moon has always been to him the lamp of wisdom, a symbol of the right way to see the world.

They walk the third-floor hall and arrive at the miniature room without incident.

When Crispin switches on the overhead lights, the chandeliers and lamps within the scale model brighten as well.

Harley has never been here before. Although he’s an unusual mutt and perhaps something more than a canine, he behaves as any dog might in a new place: He puts his nose to the floor, sniffing this way and that around the solid pedestal that supports the huge scale model.

Crispin begins with the drawing room where, on the afternoon of the feast of the archangels, the two mouse-size cats perched on the window seat and peered at him through the French panes.

At once a white feline form enters the miniature room from the hallway, races to the window seat, springs up, and blinks its little green eyes. When Crispin touches one fingertip to the window, the cat rubs its face against the inside of the pane, as though yearning for contact with him.

The boy has had more than three long years to think about this extraordinary reproduction of Theron Hall, and he is not surprised that only a single cat greets him this time. Three cats for three children. With Mirabell dead, two cats appeared to Crispin on the afternoon before Harley was chained to that altar. Now, of Clarette’s three little bastards, only one remains, therefore one cat.

As the cats were somehow reduced to three inches and imprisoned in the miniature Theron Hall, so the three children were in their own way imprisoned in the real house. The cats were avatars of Mirabell, Harley, and Crispin; and if the cats ever escaped, the children would cast off their spells and break free, too.

Now that Mirabell and Harley are dead, two cats are gone. An avatar is an embodiment of a principle. If the principle—in this case a child—ceases to exist, the avatar might cease to exist, too, if you think of the child as just an animal, a meat machine.

Every child, every human being, however, is more than just a physical presence, which Giles Gregorio and his freak-show family well know. These apostles of the dark side want not only the blood of the innocent—a perversion of “Do this in remembrance of me”—but also their souls.

When a child is murdered in a ritual act, the soul will not be condemned forever. No action of an innocent could earn damnation.

Crispin is certain, therefore, that in the way that matters most, Mirabell and Harley are still alive, their spirits imprisoned in the scale model of Theron Hall.

He has survived so that he might free them.

Years of brooding on the subject leads him to the conclusion that the souls herein don’t have the same freedom of movement within the miniature structure that the avatar cats enjoyed. If they are captive, they will be in the room that the Gregorios regard as the most important—the altar room behind the steel-slab door.

The only level of Theron Hall not represented in this model is the basement. But it must be here, hidden in the presentation plinth on which the aboveground floors now stand.

As Crispin finishes shrugging off his backpack, the dog whines softly to attract his attention.

At the south end of the thirty-five-foot model, Harley sniffs vigorously at the overhanging surbase of the plinth.

Easing the dog aside, Crispin feels under this lip … and finds the switch.

Motors purr, the structure rises from the base that supports it, and inch by inch the underground level appears. Because ceilings in the basement are at only nine feet, the fully exposed cellar measures twenty-seven inches high in one-quarter scale, and it is presented as a long expanse of poured-in-place concrete.

Crispin hurries to his backpack, removes a claw hammer from a zippered compartment, and goes around to the back—the east—side of the model.

If any of the remaining staff is on the third floor, this is the most dangerous moment of the operation. The foundation concrete through which he needs to break is phony of course, but the top three floors of the model must rest on this, so there will be some sort of structure behind the faux concrete. The noise might not be contained within this room.

He swings the face of the hammer first, caving in a swath of the basement wall, and at once he discovers that the noise he makes here will be dwarfed by the greater noise of the west basement wall of the real house sustaining damage identical to that wrought upon the model. The miniature Theron Hall and the real one shudder, and as Crispin continues to hammer, he hears great slabs of debris crash to the basement floor four stories under him.

He reverses the hammer, using the claw to tear away chunks of the wall. As supports far below in the true house groan and as the floors on every level creak and pop, he exposes the altar room in the model.

In there, a thousand flickering electric lights in a thousand tiny glass holders mimic the candles that he saw on the night that his brother was killed. He is behind the altar, having knocked aside the upside-down crucifix. He reaches into the satanic church, seizes the marble table that serves as an altar, and rips the eighteen-inch miniature from its mounts. He places it on the floor and hammers it twice, until it cracks in pieces.

At that moment, from the hole that he has made in the basement wall of the model, a flock of what he first takes to be immense white moths or bu

tterflies erupts, brushing his face, fluttering around his head. But then he sees that their wings are white dresses or choirboy robes and that they are children, some as small as six inches, the tallest perhaps twelve. There must be twenty of them. Although they appear to be laughing or singing, they make no sound, yet their joy is evident in their exuberant flight, as they soar and swoop and dance in midair.

They do not belong here now that they are freed, and they don’t linger, but quickly fade, vanishing in flight, until only the most recently imprisoned two remain.

Crispin drops the hammer and reaches out to this last pair. For only a moment, they settle upon the palm of his hand. They are his sweet sister and his beloved brother, as ever they looked, only so much smaller.

The dog stands on his hind feet, forepaws against the model plinth, eager to see.

This Mirabell and this Harley in Crispin’s hand have no weight, yet they are the heaviest thing he has ever held.

They should not linger, nor should he want to detain them. He says only, “I love you.”

The pair rise from his upturned palm, and by the grace of their flight and by a sudden golden glow just before they vanish, they seem to return to him the love that he expressed.

Things are still crashing far down in Theron Hall, and the model is trembling and tweaking.

Snatching up the hammer, Crispin hurries around to the front of the model, where the last of the three cats is still on the window seat, peering hopefully out.

After a hesitation, he taps the hammer against one of the little windows, cracking through the stiles and muntins, shattering the tiny panes.

If the cat was once a real cat, reduced to the size of a mouse to serve as an avatar, if it was a stand-in for a human soul until the soul could be captured, it is not evil. It was as ruthlessly used as Mirabell and Harley were used.

The three-inch cat leaps through the missing window, into the palm of his hand. He holds it low to allow the dog to inspect it, and Harley approves. Crispin puts the tiny cat in a jacket pocket, certain that in this mysterious world, it will be at some point an important and valued companion.

Breathless

Breathless Lightning

Lightning The Taking

The Taking The Door to December

The Door to December Odd Thomas

Odd Thomas Midnight

Midnight Whispers

Whispers Odd Interlude #2

Odd Interlude #2 The Mask

The Mask Watchers

Watchers By the Light of the Moon

By the Light of the Moon Night Chills

Night Chills Brother Odd

Brother Odd False Memory

False Memory The Darkest Evening of the Year

The Darkest Evening of the Year Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy The Good Guy

The Good Guy Hideaway

Hideaway Innocence

Innocence Your Heart Belongs to Me

Your Heart Belongs to Me Forever Odd

Forever Odd Intensity

Intensity Saint Odd

Saint Odd Dragon Tears

Dragon Tears The Husband

The Husband Final Hour

Final Hour Demon Seed

Demon Seed City of Night

City of Night From the Corner of His Eye

From the Corner of His Eye A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog

A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog Seize the Night

Seize the Night Winter Moon

Winter Moon Strange Highways

Strange Highways The Silent Corner

The Silent Corner Twilight Eyes

Twilight Eyes Velocity

Velocity The Bad Place

The Bad Place Cold Fire

Cold Fire The Whispering Room

The Whispering Room Ricochet Joe

Ricochet Joe The Crooked Staircase

The Crooked Staircase Tick Tock

Tick Tock The Face

The Face Sole Survivor

Sole Survivor Strangers

Strangers Deeply Odd

Deeply Odd Odd Interlude #3

Odd Interlude #3 The Vision

The Vision Phantoms

Phantoms Prodigal Son

Prodigal Son Odd Hours

Odd Hours Last Light

Last Light Fear Nothing

Fear Nothing Odd Interlude #1

Odd Interlude #1 One Door Away From Heaven

One Door Away From Heaven Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder

Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder The City

The City The Dead Town

The Dead Town The Voice of the Night

The Voice of the Night Dark Rivers of the Heart

Dark Rivers of the Heart The Key to Midnight

The Key to Midnight Lost Souls

Lost Souls Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever

Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever Odd Apocalypse

Odd Apocalypse Icebound

Icebound The Book of Counted Sorrows

The Book of Counted Sorrows The Neighbor

The Neighbor Ashley Bell

Ashley Bell Santa's Twin

Santa's Twin Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive The Eyes of Darkness

The Eyes of Darkness The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle Writing Popular Fiction

Writing Popular Fiction City of Night f-2

City of Night f-2 Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle What the Night Knows: A Novel

What the Night Knows: A Novel Demon Child

Demon Child Starblood

Starblood Surrounded mt-2

Surrounded mt-2 Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story) Odd Interlude

Odd Interlude The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle The City: A Novel

The City: A Novel Deeply Odd ot-7

Deeply Odd ot-7 Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story) The House of Thunder

The House of Thunder Odd Interlude ot-5

Odd Interlude ot-5 Fear That Man

Fear That Man Odd Is on Our Side

Odd Is on Our Side Relentless

Relentless A Big Little Life

A Big Little Life Hanging On

Hanging On The Forbidden Door

The Forbidden Door Dragonfly

Dragonfly The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense Final Hour (Novella)

Final Hour (Novella) The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours Odd Interlude (Complete)

Odd Interlude (Complete) The Funhouse

The Funhouse 77 Shadow Street

77 Shadow Street What the Night Knows

What the Night Knows Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel

Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel The Servants of Twilight

The Servants of Twilight Star quest

Star quest Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel

Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel Chase

Chase Eyes of Darkness

Eyes of Darkness The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single)

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single) Sussurri

Sussurri The Moonlit Mind (Novella)

The Moonlit Mind (Novella) Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel

Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel![Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/ricochet_joe_kindle_in_motion_kindle_single_preview.jpg) Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single)

Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Innocence: A Novel

Innocence: A Novel Beastchild

Beastchild A Darkness in My Soul

A Darkness in My Soul Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages

Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle

The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle Frankenstein - City of Night

Frankenstein - City of Night Shadowfires

Shadowfires Last Light (Novella)

Last Light (Novella) Frankenstein - Prodigal Son

Frankenstein - Prodigal Son Ticktock

Ticktock Dance with the Devil

Dance with the Devil You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story)

You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story) The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Darkness Under the Sun

Darkness Under the Sun Dark Of The Woods

Dark Of The Woods Dean Koontz's Frankenstein

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein Frankenstein

Frankenstein The Face of Fear

The Face of Fear Children of the Storm

Children of the Storm Mr. Murder

Mr. Murder