- Home

- Dean Koontz

Writing Popular Fiction Page 3

Writing Popular Fiction Read online

Page 3

Remember, although you are extrapolating one area of society-tax-exempt religion, population growth, racism and violence, changing morality-if that one area has come to dominate your imagined future, it will have its effect on every segment of daily life. It is your responsibility to consider that before beginning.

For example, if you were primarily concerned with writing about the total failure of law and order in the city streets after dark by the year 1990, if you were portraying a future city living in siege during the dark hours when only criminals prowl about, you would have to consider the effect of this development on these, and other, areas of human experience:

The arts: Would art forms requiring people to leave the safety of their homes after dark-legitimate theater, motion pictures, sporting events, musical concerts-die away?

Dating: Wouldn't men and women who wanted to date have to meet immediately after work, go to one or the other's apartment, and lock themselves in until dawn? And wouldn't this cause a breakdown in traditional morals?

The work day: Might the work day of the city man be changed, running from dawn until eight hours later, to allow him to adjust to this kind of hostile environment?

The family: Would people be as anxious to bring children into the world as they are today, if they were bringing them into such a nasty place? Or would the Old-World family unit be restored? After all, a woman would need a man to protect her against the more adventuresome criminals who might try breaking into fortified apartments and houses, and she would have to relinquish at least a little of her new-found liberation, for strictly biological reasons.

Factories: Production plants that now work around the clock, with three different shifts, would either have to close down during darkness, or provide sleeping facilities for one whole shift that would work through most of the dark hours but couldn't go home immediately when their shift was over.

Fire protection: How would firemen, forced to answer an alarm in the night, assure their own safety? Fire trucks like tanks? Armoured suits?

Rural life: Would those people living in the relatively peaceful rural areas be overwhelmed by city-dwellers anxious to escape their beleaguered metropolises? Would country people ban together to forcefully prevent such immigration? Or would the city people stick it out, holding on to their way of life, refusing to opt for the rural way?

Criminals themselves: Who would they prey on, in the dark hours, if most citizens were behind bolted doors and armoured windows? Each other?

Politics: Would demagogues rise to power on the national level, promising law and order and delivering dictatorship? Would national leadership choose to ignore the plight of the cities? Would some cities, in anger at the federal government's apathy, secede from the country-or form their own outlaw states? Would dictators arise in these city-states? Would none of this happen and, instead, the breakdown in law and order during darkness be considered just another "burden" of city life as, today, metropolitan residents view outrageous pollution and overpopulation?

Broadcast media: With more people staying home at nights, would the broadcast media become even more popular? With the larger audience, would new forms of broadcast media-other than radio and standard television-be put on the market? Three-dimensional television? Total sensory television? Home motion picture tape systems?

From this list, you can see that, though you may be extrapolating chiefly one thing, that single exaggerated social factor will have a pronounced effect on every facet of daily life.

ALIEN CONTACT STORY

The second plot type in science fiction is the alien contact story. This includes invasions of the Earth like H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, though, as mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, this kind of fright story is presently out of vogue. More subtle and therefore more terrifying invasion stories, like John Christopher's The Possessors, are far more acceptable to today's readers: stories, in brief, in which only a few people-perhaps only a single household or individual-may ever know about the alien presence, in which the threat of world conquest is not dramatized in melodramatic terms, but in human ones. The alien contact story also includes novels about voyages of Earthmen to other worlds, and even stories in which the alien is a man from so far in the future of our own Earth that he is either mentally, physically, or both mentally and physically unlike a man. A good novel in this vein is Robert Silverberg's The Masks of Time, which deals with a physically perfect man from the future whose mind is strangely different from our own, his attitudes quite unlike ours.

Putting aside the man from the far future device-since it is rarely used-we see that all other aliens are extraterrestrial in nature, beings from other worlds and other galaxies, even other universes. No matter what the nature of the alien being, you can handle it in two ways. First, you may construct a creature which has evolved under entirely different circumstances than mankind has. Perhaps it's an alien from a world with many times our gravity. (Hal Clement's Mission of Gravity is a classic with this kind of background. ) Perhaps it comes from a world where the atmosphere is predominately methane or some other substance toxic to man. The possibilities are limitless. If you choose this path, you must thoroughly research-through science books-what such a world would be like, extrapolating from what present-day facts you can find. Then, you must learn what effects such strange conditions would have on the evolution of a species. Only then can you hope to convince the reader of the validity of your vision.

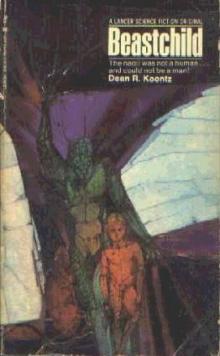

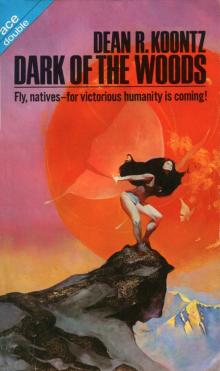

The second way to handle your alien is to have him originate on a world essentially like our own Earth, but to have him be a member of another species-besides the ape, from which man most likely descended-such as a lizard-man (my own Beastchild creates a sympathetic alien of reptillian nature), a winged man, a creature of the seas, a nocturnal, four-legged predator, or any of countless other possibilities. Robert Silverberg's excellent Downward to the Earth postulates intelligent, elephant-like creatures on an Earth-type world. A. E. van Vogt's Voyage of the Space Beagle contains a catlike alien that can pass, unchanged, through walls or any other barriers, and my own Dark of the Woods is set on an Earth-like world where the native race is a diminutive and delicate human-variant with gossamer and functional wings.

This second method-creating an alien who comes from an Earth-type world and breathes Earth-mixture atmosphere-helps you avoid a great deal of research, while providing a suitably eerie extra-terrestrial being. You don't have to probe in science books if he comes from an Earth-type world-you already know much about him. You can concentrate, now, on extrapolating his physical looks and his culture.

At this point, considering your plot and your ability, you must decide whether the alien will be handled as a serious character or as a figure for satire and buffoonery. Unless your writing talents are well developed, and unless you are very familiar with science fiction, you should avoid the latter approach. You may think it a simple matter to create a comic alien with too many legs, several eyes, and a squeaky voice, imbue him with a crackpot sense of humor (we all think of ourselves as the master of the funny line, even if we write tear jerkers for a living), and push him on stage. This way lies disaster. Only one writer in recent years has proven continually adept at creating funny aliens and using them to advantage: Keith Laumer's many books, including his Retief novels about an Earth diplomat mixed up in galactic intrigues, usually escape crossing that line between humor and boredom.

If you intend to develop your alien as a serious character-in either the role of a menacing antagonist or as a compatriot of the hero-you should delve as deeply into the alien's psyche and personality as you would into a human's. Extra-terrestrials do not invade the Earth without purpose-indeed, they should have doubts, aspirations, second thoughts, loves, hates, and prejudices-unless they are megalomaniacs. Also remember that an alien creature, while having motivations just as humans do, will have substantially different motivations. Suppose, for instance, that the alien comes from a society where the institution of the family is unheard of, where breeding is a

more natural process and less of a personal one than it is with human beings. The effects upon various motivations will be profound.

Examples of alien characterization, as well as other requirements peculiar to science fiction, will be given later in this chapter.

TIME TRAVEL STORY

The third plot type in science fiction is the time travel story. Ever since H. G. Wells created the form with The Time Machine, readers have evidenced a continuing interest in the subject. One reason for this popularity is that the science of time-space is so esoteric, so intangible, that a writer can formulate a "wonderful new discovery" to justify the existence of the time machine and place his story at any point in history: today, tomorrow, next week, a hundred years from now, or a hundred years ago, making for varied and vivid backgrounds and plots. Too, because time travel stories deal with a quantity which people are familiar with-minutes, hours, memories-it seems more real than a story based on science beyond their understanding.

A time machine can operate in several ways. If the story purpose is best suited by a machine that will only carry passengers into the past (Harry Harrison's The Technicolor Time Machine), the writer need only say so. If he wants a machine that only travels into the future (Wilson Tucker's The Year of the Quiet Sun) and then back to the starting point, or if he wants a machine capable of forward and backward time travel, he need only inform the reader, briefly, of the machine's limitations or abilities.

Trips into the future require the same extrapolated background we have discussed. Trips into the past require a background for the proper period; this can easily be researched in any library with a good selection of historical reference texts.

Only one main brand of error is endemic to the time travel tale: the time paradox. The term is best explained through examples, which are limitless. For instance:

If you traveled back to last Thursday morning in a time machine and met yourself back then and told yourself to invest in a certain company because their stock would soar during the next week, what would happen if the Early You did as the Later You wished? When the Later You returned to the present, would he find himself rich? Or perhaps, while the Early You was running to the stock broker, he was stricken by an automobile and suffered two broken legs. When the Later You returned to the present, would he find himself with two broken legs? Perhaps you would end up hospitalized, never having been able to make the trip in the first place because your legs were broken a week ago. Yet, if you had never taken the time trip, you wouldn't have sent your Early Self into the path of the car and would not have broken legs. Yet, if you did make the trip, and had the broken legs, you couldn't have made the trip because of the broken legs and…

Do you see what a time paradox is?

Here's another:

Suppose your hero went back in time and killed the villain ten years in the past. The villain would cease to exist at that point. Any children he had fostered would cease to exist if they had not been fathered before that day ten years ago. Did you really mean to kill his innocent children as well as him?

Or suppose you traveled back in time and married your great-grandmother. Would you be your own great-grandfather?

If you returned again and again to the same general period in time, wouldn't there be a whole crowd of you walking around?

If you go into the future and see something unpleasant in your own life, and you come back to the present to make sure that the future thing never happens-can you really hope to change the future? If you've already seen yourself dying in a wrecked automobile, can you return to the present and avoid that accident? If you've seen it, isn't it already predestined?

To better understand the complications you must deal with in the time travel story, read Up the Line, a modern classic of the form by Robert Silverberg, published by Ballantine Books. Silverberg purposefully generates every conceivable time paradox and carries them all to their wildly absurd and fascinating conclusion.

NEW DISCOVERY STORY

If you don't feel up to the confusion of time travel, perhaps the fourth type of science fiction plot will intrigue you: the new discovery story. First, you conjecture a new discovery-it may be a device, process, or simply a theory-which would revolutionize modern life. You then concern yourself with detailing the effects that discovery has on society and, more immediately, upon your small cast of characters.

Harry Harrison's The Daleth Effect deals with the discovery of a simple, relatively inexpensive stardrive which will permit space travel at a ridiculously low cost. Suddenly, the stars are ours-not in thirty or fifty or a hundred years, but now. The powerful social force of this process or device (Harrison never makes that entirely clear) spreads antagonism among world governments, because if any one country owned the Daleth Effect, it would soon so dominate as to make other nations powerless.

Wilson Tucker's Wild Talent deals with the emergence of ESP abilities in the first of a new breed of human beings and details the fear and doubt such a discovery would cause in today's society.

It is not essential, in the new discovery story, to adequately explain, through present-day science or pseudo-scientific double-talk, how the discovery works. It is always preferable, of course, to ground the device in a bedrock of acceptable scientific theory. But this type of science fiction story is far more concerned with the "how" and the "what" than with the technical-theoretical "why." And, since it usually takes place in the present or the very near future, it is the story type which requires the least amount of extrapolation and research. Indeed, many new discovery science fiction novels are set in such a near future that they are not labeled as science fiction, but as suspense: Michael Crichton's best-selling The Andromeda Strain, and The Tashkent Crisis by William Craig.

SCIENTIFIC PROBLEM STORY

Fifth, we have the scientific problem story.. This form is actually best suited to the short story, unless the problem the characters must solve is so complex, with so many ramifications, that the novel length is justified. In this form, the author confronts his hero with a seemingly insoluble scientific problem and forces him to use his wits to overcome staggering odds.

A typical sort of problem story might be this: The hero has landed his spaceship on an uninhabited, lifeless world, without benefit of his rockets which are out of order. As he fixes the engines, he discovers the planet's atmosphere is combustible, of a gasoline-like vapor. If he had landed with the rockets blazing, the entire kaboodle would have exploded; he was lucky. But, now that he's down, how in the devil can he take off again? Even if the engines are repaired, can they lift off without igniting the atmosphere around them and completely destroying themselves in the resultant explosion? One answer is this: Since the atmosphere is composed of gasoline-like vapor, and is not pure oxygen, it cannot explode; there is simply nowhere for the expanding vapor to explode to. All it can do is burn, and that cannot harm them at all as long as they remain inside their escaping, steel ship.

Unfortunately, the problem story leaves room for little more than adequate characterization, and the plot is severely constricted by the necessity to solve the main, center-stage problem which usually concerns, not people, but a scientific phenomenon. Many well-known science fiction writers began with problem stories, but Hal Clement (Mission of Gravity, Star Light) is the only writer to have made a solid career from them.

ALTERED PAST STORY

Sixth, we have the altered past story. These tales are based on the notion that the world would have been substantially different than it is, if some ma/or historical event had not happened, or if it had been reversed. For example, Philip K. Dick wrote a masterful Hugo Award-winning novel (The Hugo is the science fiction world's equivalent of the Oscar) The Man in the High Castle, which dealt with a world in which Germany and Japan won World War II and split the United States between them. That idea, clearly, is staggering. Keith Roberts' Pavanne tells the story of a world in which England did not defeat the Spanish Armada, Spain Catholicized England, and the Middle Ages, when science

was considered necromancy and was banned, have never ended.

The wealth of story ideas is obvious. What if the South had won the Civil War? What if America had lost the Revolutionary War? What if a nuclear war had been fought in 1958? What if Lincoln had not been assassinated?

The new science fiction writer should be warned that the research required to write such a "period" science fiction novel is intense indeed. Before you can project how things would have developed since the historical event was rewritten, you must know how things really were back then, what forces would have filled the vacuum, what philosophy would have replaced the dead ones, what persons would have replaced the assassinated greats.

ALTERNATE WORLDS STORY

Akin to the sixth type is the seventh type of science fiction story: the alternate worlds story. Imagine that, in the beginning, there was only one Earth but that different possible Earths branched off from ours at various points in time. Let's say that every time something could have happened two different ways, another possibility world came into being. On our world, there was a World War I which the Allies won; in another world, the Allies lost; in our world, we did not avoid the Second World War; in a third world, they did; in a fourth world, the U.S. got into World War II, and lost to the Germans who took possession of America, giving the course of history yet another turn. So on, and on, and on. The result is a vast, indeed an infinite number of possible Earths existing side-by-side, each invisible to the other but nonetheless real. This is, basically, the theory of other dimensions beyond our own, dimensions in a romantic sense rather than the mathematical. Specific science fiction novels that deal with alternate worlds include: my own Hell's Gate; Worlds of the Imperium, The Time Benders, and The Other Side of Time by Keith Laumer; The Gate of Time by Philip Jose Farmer; and The Wrecks of Time by Michael Moorcock.

Breathless

Breathless Lightning

Lightning The Taking

The Taking The Door to December

The Door to December Odd Thomas

Odd Thomas Midnight

Midnight Whispers

Whispers Odd Interlude #2

Odd Interlude #2 The Mask

The Mask Watchers

Watchers By the Light of the Moon

By the Light of the Moon Night Chills

Night Chills Brother Odd

Brother Odd False Memory

False Memory The Darkest Evening of the Year

The Darkest Evening of the Year Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy The Good Guy

The Good Guy Hideaway

Hideaway Innocence

Innocence Your Heart Belongs to Me

Your Heart Belongs to Me Forever Odd

Forever Odd Intensity

Intensity Saint Odd

Saint Odd Dragon Tears

Dragon Tears The Husband

The Husband Final Hour

Final Hour Demon Seed

Demon Seed City of Night

City of Night From the Corner of His Eye

From the Corner of His Eye A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog

A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog Seize the Night

Seize the Night Winter Moon

Winter Moon Strange Highways

Strange Highways The Silent Corner

The Silent Corner Twilight Eyes

Twilight Eyes Velocity

Velocity The Bad Place

The Bad Place Cold Fire

Cold Fire The Whispering Room

The Whispering Room Ricochet Joe

Ricochet Joe The Crooked Staircase

The Crooked Staircase Tick Tock

Tick Tock The Face

The Face Sole Survivor

Sole Survivor Strangers

Strangers Deeply Odd

Deeply Odd Odd Interlude #3

Odd Interlude #3 The Vision

The Vision Phantoms

Phantoms Prodigal Son

Prodigal Son Odd Hours

Odd Hours Last Light

Last Light Fear Nothing

Fear Nothing Odd Interlude #1

Odd Interlude #1 One Door Away From Heaven

One Door Away From Heaven Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder

Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder The City

The City The Dead Town

The Dead Town The Voice of the Night

The Voice of the Night Dark Rivers of the Heart

Dark Rivers of the Heart The Key to Midnight

The Key to Midnight Lost Souls

Lost Souls Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever

Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever Odd Apocalypse

Odd Apocalypse Icebound

Icebound The Book of Counted Sorrows

The Book of Counted Sorrows The Neighbor

The Neighbor Ashley Bell

Ashley Bell Santa's Twin

Santa's Twin Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive The Eyes of Darkness

The Eyes of Darkness The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle Writing Popular Fiction

Writing Popular Fiction City of Night f-2

City of Night f-2 Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle What the Night Knows: A Novel

What the Night Knows: A Novel Demon Child

Demon Child Starblood

Starblood Surrounded mt-2

Surrounded mt-2 Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story) Odd Interlude

Odd Interlude The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle The City: A Novel

The City: A Novel Deeply Odd ot-7

Deeply Odd ot-7 Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story) The House of Thunder

The House of Thunder Odd Interlude ot-5

Odd Interlude ot-5 Fear That Man

Fear That Man Odd Is on Our Side

Odd Is on Our Side Relentless

Relentless A Big Little Life

A Big Little Life Hanging On

Hanging On The Forbidden Door

The Forbidden Door Dragonfly

Dragonfly The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense Final Hour (Novella)

Final Hour (Novella) The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours Odd Interlude (Complete)

Odd Interlude (Complete) The Funhouse

The Funhouse 77 Shadow Street

77 Shadow Street What the Night Knows

What the Night Knows Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel

Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel The Servants of Twilight

The Servants of Twilight Star quest

Star quest Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel

Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel Chase

Chase Eyes of Darkness

Eyes of Darkness The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single)

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single) Sussurri

Sussurri The Moonlit Mind (Novella)

The Moonlit Mind (Novella) Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel

Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel![Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/ricochet_joe_kindle_in_motion_kindle_single_preview.jpg) Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single)

Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Innocence: A Novel

Innocence: A Novel Beastchild

Beastchild A Darkness in My Soul

A Darkness in My Soul Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages

Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle

The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle Frankenstein - City of Night

Frankenstein - City of Night Shadowfires

Shadowfires Last Light (Novella)

Last Light (Novella) Frankenstein - Prodigal Son

Frankenstein - Prodigal Son Ticktock

Ticktock Dance with the Devil

Dance with the Devil You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story)

You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story) The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Darkness Under the Sun

Darkness Under the Sun Dark Of The Woods

Dark Of The Woods Dean Koontz's Frankenstein

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein Frankenstein

Frankenstein The Face of Fear

The Face of Fear Children of the Storm

Children of the Storm Mr. Murder

Mr. Murder