- Home

- Dean Koontz

Winter Moon Page 4

Winter Moon Read online

Page 4

She closed her eyes too, so she wouldn’t have to look at poor Louie’s face pressed to the window in the door. So gray, his face, so drawn and gray. He loved Jack too. Poor Louie.

She chewed on her lower lip and squeezed her eyes tightly shut and held the phone in both hands against her chest, searching for the strength she was going to need, praying for the strength.

She heard a key in the back door. Louie knew where they hid the spare on the porch.

The door opened. He came inside with the sound of rain swelling behind him. “Heather,” he said.

The sound of the rain. The rain. The cold merciless sound of the rain.

CHAPTER FOUR

The Montana morning was high and blue, pierced by mountains with peaks as white as angels’ robes, graced by forests green and by the smooth contours of lower meadows still asleep under winter’s mantle. The air was pure and so clear it seemed possible to look all the way to China if not for the obstructing terrain.

Eduardo Fernandez stood on the front porch of the ranch house, staring across the down-sloping, snow-covered fields to the woods a hundred yards to the east. Sugar pines and yellow pines crowded close to one another and pinned inky shadows to the ground, as if the night never quite escaped their needled grasp even with the rising of a bright sun in a cloudless sky.

The silence was deep. Eduardo lived alone, and his nearest neighbor was two miles away. The wind was still abed, and nothing moved across that vast panorama except for two birds of prey—hawks, perhaps—circling soundlessly high overhead.

Shortly after one o’clock in the morning, when the night usually would have been equally steeped in silence, Eduardo had been awakened by a strange sound. The longer he had listened, the stranger it had seemed. As he had gotten out of bed to seek the source, he had been surprised to find he was afraid. After seven decades of taking what life threw at him, having attained spiritual peace and an acceptance of the inevitability of death, he’d not been frightened of anything in a long time. He was unnerved, therefore, when last night he had felt his heart thudding furiously and his gut clenching with dread merely because of a queer sound.

Unlike many seventy-year-old men, Eduardo rarely had difficulty attaining plumbless sleep for a full eight hours. His days were filled with physical activity, his evenings with the solace of good books; a lifetime of measured habits and moderation left him vigorous in old age, without troubling regrets, content. Loneliness was the only curse of his life, since Margarite had died three years before, and on those infrequent occasions when he woke in the middle of the night, it was a dream of his lost wife that harried him from sleep.

The sound had been less loud than all-pervasive. A low throbbing that swelled like a series of waves rushing toward a beach. Beneath the throbbing, an undertone that was almost subliminal, quaverous, an eerie electronic oscillation. He’d not only heard it but felt it, vibrating in his teeth, his bones. The glass in the windows hummed with it. When he placed a hand flat against the wall, he swore that he could feel the waves of sound cresting through the house itself, like the slow beating of a heart beneath the plaster.

Accompanying that pulse had been a sense of pressure, as if he had been listening to someone or something rhythmically straining against confinement, struggling to break out of a prison or through a barrier.

But who?

Or what?

Eventually, after scrambling out of bed, pulling on pants and shoes, he had gone onto the front porch, where he had seen the light in the woods. No, he had to be more honest with himself. It hadn’t been merely a light in the woods, nothing as simple as that.

He wasn’t superstitious. Even as a young man, he had prided himself on his levelheadedness, common sense, and unsentimental grasp of the realities of life. The writers whose books lined his study were those with a crisp, simple style and with no patience for fantasy, men with a cold clear vision, who saw the world for what it was and not for what it might be: men like Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Ford Madox Ford.

The phenomenon in the lower woods was nothing that his favorite writers—every last one of them a realist—could have incorporated into their stories. The light had not been from an object within the forest, against which the pines had been silhouetted; rather, it had come from the pines themselves, mottled amber radiance that appeared to originate within the bark, within the boughs, as if the tree roots had siphoned water from a subterranean pool contaminated by a greater percentage of radium than the paint with which watch dials had once been coated to allow time to be told in the dark.

A cluster of ten to twenty pines had been involved. Like a glowing shrine in the otherwise night-black fastness of timber.

Unquestionably, the mysterious source of the light was also the source of the sound. When the former had begun to fade, so had the latter. Quieter and dimmer, quieter and dimmer. The March night had become silent and dark again in the same instant, marked only by the sound of his own breathing and illuminated by nothing stranger than the silver crescent of a quarter moon and the pearly phosphorescence of the snow-shrouded fields.

The event had lasted about seven minutes.

It had seemed much longer.

Back inside the house, he had stood at the windows, waiting to see what would happen next. Eventually, when that seemed to have been the sum of it, he returned to bed.

He had not been able to get back to sleep. He had lain awake…wondering.

Every morning he sat down to breakfast at six-thirty, with his big shortwave radio tuned to a station in Chicago that provided international news twenty-four hours a day. The peculiar experience during the previous night hadn’t been a sufficient interruption of the rhythms of his life to make him alter his schedule. This morning he’d eaten the entire contents of a large can of grapefruit sections, followed by two eggs over easy, home fries, a quarter pound of bacon, and four slices of buttered toast. He hadn’t lost his hearty appetite with age, and a lifelong dedication to the foods that were hardest on the heart had only left him with the constitution of a man more than twenty years his junior.

Finished eating, he always liked to linger over several cups of black coffee, listening to the endless troubles of the world. The news unfailingly confirmed the wisdom of living in a far place with no neighbors in view.

This morning, though he had lingered longer than usual with his coffee, and though the radio had been on, he hadn’t been able to remember a word of the news when he pushed back his chair and got up from breakfast. The entire time, he had been studying the woods through the window beside the table, trying to decide if he should go down to the foot of the meadow and search for evidence of the enigmatic visitation.

Now, standing on the front porch in knee-high boots, jeans, sweater, and sheepskin-lined jacket, wearing a cap with fur-lined earflaps tied under his chin, he still hadn’t decided what he was going to do.

Incredibly, fear was still with him. Bizarre as they might have been, the tides of pulsating sound and the luminosity in the trees had not harmed him. Whatever threat he perceived was entirely subjective, no doubt more imaginary than real.

Finally he became sufficiently angry with himself to break the chains of dread. He descended the porch steps and strode across the front yard.

The transition from yard to meadow was hidden under a cloak of snow six to eight inches deep in some places and knee-high in others, depending on where the wind had scoured it away or piled it. After thirty years on the ranch, he was so familiar with the contours of the land and the ways of the wind that he unthinkingly chose the route that offered the least resistance.

White plumes of breath steamed from him. The bitter air brought a pleasant flush to his cheeks. He calmed himself by concentrating on—and enjoying—the familiar effects of a winter day.

He stood for a while at the end of the meadow, studying the very trees that, last night, had glowed a smoky amber against the black backdrop of the deeper woods, as if they had been imbued with a divine presence, like

God in the bush that burned without being consumed. This morning they looked no more special than a million other sugar and ponderosa pines, the former somewhat greener than the latter.

The specimens at the edge of the forest were younger than those rising behind them, only about thirty to thirty-five feet tall, as young as twenty years. They had grown from seeds fallen to the earth when he had already been on the ranch a decade, and he felt as if he knew them more intimately than he had known most people in his life.

The woods had always seemed like a cathedral to him. The trunks of the great evergreens were reminiscent of the granite columns of a nave, soaring high to support a vaulted ceiling of green boughs. The pine-scented silence was ideal for meditation. Walking the meandering deer trails, he often had a sense that he was in a sacred place, that he was not just a man of flesh and bone but an heir to eternity.

He had always felt safe in the woods.

Until now.

Stepping out of the meadow and into the random-patterned mosaic of shadows and sunlight beneath the interlaced pine branches, Eduardo found nothing out of the ordinary. Neither the trunks nor the boughs showed signs of heat damage, no charring, not even a singed curl of bark or blackened cluster of needles. The thin layer of snow under the trees had not melted anywhere, and the only tracks in it were those of deer, raccoon, and smaller animals.

He broke off a piece of bark from a sugar pine and crumbled it between the thumb and forefinger of his gloved right hand. Nothing unusual about it.

He moved deeper into the woods, past the place where the trees had stood in radiant splendor in the night. Some of the older pines were over two hundred feet tall. The shadows grew more numerous and blacker than ash buds in the front of March, while the sun found fewer places to intrude.

His heart would not be still. It thudded hard and fast.

He could find nothing in the woods but what had always been there, yet his heart would not be still.

His mouth was dry. The full curve of his spine was clad in a chill that had nothing to do with the wintry air.

Annoyed with himself, Eduardo turned back toward the meadow, following the tracks he had left in the patches of snow and the thick carpet of dead pine needles. The crunch of his footsteps disturbed a slumbering owl from its secret perch in some high bower.

He felt a wrongness in the woods. He couldn’t put a finer point on it than that. Which sharpened his annoyance. A wrongness. What the hell did that mean? A wrongness.

The hooting owl.

Spiny black pine cones on white snow.

Pale beams of sunlight lancing through the gaps in the gray-green branches.

All of it ordinary. Peaceful. Yet wrong.

As he returned to the perimeter of the forest, with snow-covered fields visible between the trunks of the trees ahead, he was suddenly certain that he was not going to reach open ground, that something was rushing at him from behind, some creature as indefinable as the wrongness that he sensed around him. He began to move faster. Fear swelled step by step. The hooting of the owl seemed to sour into a cry as alien as the shriek of a nemesis in a nightmare. He stumbled on an exposed root, his heart trip-hammered, and he spun around with a cry of terror to confront whatever demon was in pursuit of him.

He was, of course, alone.

Shadows and sunlight.

The hoot of an owl. A soft and lonely sound. As ever.

Cursing himself, he headed for the meadow again. Reached it. The trees were behind him. He was safe.

Then, dear sweet Jesus, the fear again, worse than ever, the absolute dead certainty that it was coming—what?—that it was for sure gaining on him, that it would drag him down, that it was bent upon committing an act infinitely worse than murder, that it had an inhuman purpose and unknown uses for him so strange they were beyond both his understanding and conception. This time he was in the grip of a terror so black and profound, so mindless, that he could not summon the courage to turn and confront the empty day behind him—if, indeed, it proved to be empty this time. He raced toward the house, which appeared far more distant than a hundred yards, a citadel beyond his reach. He kicked through shallow snow, blundered into deeper drifts, ran and churned and staggered and flailed uphill, making wordless sounds of blind panic—“Uh, uh, uhhhhh, uh, uh”—all intellect repressed by instinct, until he found himself at the porch steps, up which he scrambled, at the top of which he turned, at last, to scream—“No!”—at the clear, crisp, blue Montana day.

The pristine mantle of snow across the broad field was marred only by his own trail to and from the woods.

He went inside.

He bolted the door.

In the big kitchen he stood for a long time in front of the brick fireplace, still dressed for the outdoors, basking in the heat that poured across the hearth—yet unable to get warm.

Old. He was an old man. Seventy. An old man who had lived alone too long, who sorely missed his wife. If senility had crept up on him, who was around to notice? An old, lonely man with cabin fever, imagining things.

“Bullshit,” he said after a while.

He was lonely, all right, but he wasn’t senile.

After stripping out of his hat, coat, gloves, and boots, he got the hunting rifles and shotguns out of the locked cabinet in the study. He loaded all of them.

CHAPTER FIVE

Mae Hong, who lived across the street, came over to take care of Toby. Her husband was a cop too, though not in the same division as Jack. Because the Hongs had no children of their own yet, Mae was free to stay as late as necessary, in the event Heather needed to put in a long vigil at the hospital.

While Louie Silverman and Mae remained in the kitchen, Heather lowered the sound on the television and told Toby what had happened. She sat on the footstool, and after tossing the blankets aside, he perched on the edge of the chair. She held his small hands in hers.

She didn’t share the grimmest details with him, in part because she didn’t know all of them herself but also because an eight-year-old could handle only so much. On the other hand, she couldn’t gloss over the situation, either, because they were a police family. They lived with the repressed expectation of just such a disaster as had struck that morning, and even a child had the need and the right to know when his father had been seriously wounded.

“Can I go to the hospital with you?” Toby asked, holding more tightly to her hands than he probably realized.

“It’s best for you to stay here right now, honey.”

“I’m not sick any more.”

“Yes, you are.”

“I feel good.”

“You don’t want to give your germs to your dad.”

“He’ll be all right, won’t he?”

She could give him only one answer even if she couldn’t be certain it would prove to be correct. “Yes, baby, he’s going to be all right.”

His gaze was direct. He wanted the truth. Right at that moment he seemed to be far older than eight. Maybe cops’ kids grew up faster than others, faster than they should.

“You’re sure?” he said.

“Yes. I’m sure.”

“W-where was he shot?”

“In the leg.”

Not a lie. It was one of the places he was shot. In the leg and two hits in the torso, Crawford had said. Two hits in the torso. Jesus. What did that mean? Take out a lung? Gutshot? The heart? At least he hadn’t sustained head wounds. Tommy Fernandez had been shot in the head, no chance.

She felt a sob of anguish rising in her, and she strained to force it down, didn’t dare give voice to it, not in front of Toby.

“That’s not so bad, in the leg,” Toby said, but his lower lip was trembling. “What about the bad guy?”

“He’s dead.”

“Daddy got him?”

“Yes, he got him.”

“Good,” Toby said solemnly.

“Daddy did what was right, and now we have to do what’s right too, we have to be strong. Okay?”

; “Yeah.”

He was so small. It wasn’t fair to put such a weight on a boy so small.

She said, “Daddy needs to know we’re okay, that we’re strong, so he doesn’t have to worry about us and can concentrate on getting well.”

“Sure.”

“That’s my boy.” She squeezed his hands. “I’m real proud of you, do you know that?”

Suddenly shy, he looked at the floor. “Well…I’m…I’m proud of Daddy.”

“You should be, Toby. Your dad’s a hero.”

He nodded but couldn’t speak. His face was screwed up as he strained to avoid tears.

“You be good for Mae.”

“Yeah.”

“I’ll be back as soon as I can.”

“When?”

“As soon as I can.”

He sprang off the chair, into her arms, so fast and with such force he almost knocked her off the stool. She hugged him fiercely. He was shuddering as if with fever chills, though that stage of his illness had passed almost two days ago. Heather squeezed her eyes shut, bit down on her tongue almost hard enough to draw blood, being strong, being strong even if, damn it, no one should ever have to be so strong.

“Gotta go,” she said softly.

Toby pulled back from her.

She smiled at him, smoothed his tousled hair.

He settled into the armchair and propped his legs on the stool again. She tucked the blankets around him, then turned the sound up on the television once more.

Elmer Fudd trying to terminate Bugs Bunny. Cwazy wabbit. Boom-boom, bang-bang, whapitta-whapittawhap, thud, clunk, hoo-ha, around and around in perpetual pursuit.

In the kitchen, Heather hugged Mae Hong and whispered, “Don’t let him watch any regular channels, where he might see a news brief.”

Mae nodded. “If he gets tired of cartoons, we’ll play games.”

“Those bastards on the TV news, they always have to show you the blood, get the ratings. I don’t want him seeing his father’s blood on the ground.”

The storm washed all the color out of the day. The sky was as charry as burned-out ruins, and from a distance of even half a block, the palm trees looked black. Wind-driven rain, gray as iron nails, hammered every surface, and gutters overflowed with filthy water.

Breathless

Breathless Lightning

Lightning The Taking

The Taking The Door to December

The Door to December Odd Thomas

Odd Thomas Midnight

Midnight Whispers

Whispers Odd Interlude #2

Odd Interlude #2 The Mask

The Mask Watchers

Watchers By the Light of the Moon

By the Light of the Moon Night Chills

Night Chills Brother Odd

Brother Odd False Memory

False Memory The Darkest Evening of the Year

The Darkest Evening of the Year Life Expectancy

Life Expectancy The Good Guy

The Good Guy Hideaway

Hideaway Innocence

Innocence Your Heart Belongs to Me

Your Heart Belongs to Me Forever Odd

Forever Odd Intensity

Intensity Saint Odd

Saint Odd Dragon Tears

Dragon Tears The Husband

The Husband Final Hour

Final Hour Demon Seed

Demon Seed City of Night

City of Night From the Corner of His Eye

From the Corner of His Eye A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog

A Big Little Life: A Memoir of a Joyful Dog Seize the Night

Seize the Night Winter Moon

Winter Moon Strange Highways

Strange Highways The Silent Corner

The Silent Corner Twilight Eyes

Twilight Eyes Velocity

Velocity The Bad Place

The Bad Place Cold Fire

Cold Fire The Whispering Room

The Whispering Room Ricochet Joe

Ricochet Joe The Crooked Staircase

The Crooked Staircase Tick Tock

Tick Tock The Face

The Face Sole Survivor

Sole Survivor Strangers

Strangers Deeply Odd

Deeply Odd Odd Interlude #3

Odd Interlude #3 The Vision

The Vision Phantoms

Phantoms Prodigal Son

Prodigal Son Odd Hours

Odd Hours Last Light

Last Light Fear Nothing

Fear Nothing Odd Interlude #1

Odd Interlude #1 One Door Away From Heaven

One Door Away From Heaven Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder

Koontz, Dean R. - Mr. Murder The City

The City The Dead Town

The Dead Town The Voice of the Night

The Voice of the Night Dark Rivers of the Heart

Dark Rivers of the Heart The Key to Midnight

The Key to Midnight Lost Souls

Lost Souls Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever

Odd Thomas: You Are Destined To Be Together Forever Odd Apocalypse

Odd Apocalypse Icebound

Icebound The Book of Counted Sorrows

The Book of Counted Sorrows The Neighbor

The Neighbor Ashley Bell

Ashley Bell Santa's Twin

Santa's Twin Dead and Alive

Dead and Alive The Eyes of Darkness

The Eyes of Darkness The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle Writing Popular Fiction

Writing Popular Fiction City of Night f-2

City of Night f-2 Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein 4-Book Bundle What the Night Knows: A Novel

What the Night Knows: A Novel Demon Child

Demon Child Starblood

Starblood Surrounded mt-2

Surrounded mt-2 Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #3 (An Odd Thomas Story) Odd Interlude

Odd Interlude The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle

The Odd Thomas Series 7-Book Bundle The City: A Novel

The City: A Novel Deeply Odd ot-7

Deeply Odd ot-7 Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story)

Odd Interlude #1 (An Odd Thomas Story) The House of Thunder

The House of Thunder Odd Interlude ot-5

Odd Interlude ot-5 Fear That Man

Fear That Man Odd Is on Our Side

Odd Is on Our Side Relentless

Relentless A Big Little Life

A Big Little Life Hanging On

Hanging On The Forbidden Door

The Forbidden Door Dragonfly

Dragonfly The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense Final Hour (Novella)

Final Hour (Novella) The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours

The Odd Thomas Series 4-Book Bundle: Odd Thomas, Forever Odd, Brother Odd, Odd Hours Odd Interlude (Complete)

Odd Interlude (Complete) The Funhouse

The Funhouse 77 Shadow Street

77 Shadow Street What the Night Knows

What the Night Knows Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel

Deeply Odd: An Odd Thomas Novel The Servants of Twilight

The Servants of Twilight Star quest

Star quest Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel

Frankenstein Dead and Alive: A Novel Chase

Chase Eyes of Darkness

Eyes of Darkness The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single)

The Moonlit Mind: A Tale of Suspense (Kindle Single) Sussurri

Sussurri The Moonlit Mind (Novella)

The Moonlit Mind (Novella) Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel

Frankenstein: Lost Souls - A Novel![Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/05/ricochet_joe_kindle_in_motion_kindle_single_preview.jpg) Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single)

Ricochet Joe [Kindle in Motion] (Kindle Single) Innocence: A Novel

Innocence: A Novel Beastchild

Beastchild A Darkness in My Soul

A Darkness in My Soul Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages

Oddkins: A Fable for All Ages The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle

The Frankenstein Series 5-Book Bundle Frankenstein - City of Night

Frankenstein - City of Night Shadowfires

Shadowfires Last Light (Novella)

Last Light (Novella) Frankenstein - Prodigal Son

Frankenstein - Prodigal Son Ticktock

Ticktock Dance with the Devil

Dance with the Devil You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story)

You Are Destined to Be Together Forever (Short Story) The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense

The Moonlit Mind (Novella): A Tale of Suspense Darkness Under the Sun

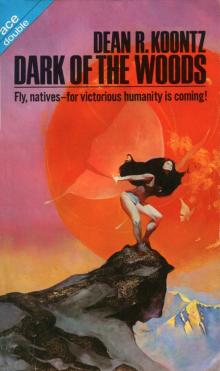

Darkness Under the Sun Dark Of The Woods

Dark Of The Woods Dean Koontz's Frankenstein

Dean Koontz's Frankenstein Frankenstein

Frankenstein The Face of Fear

The Face of Fear Children of the Storm

Children of the Storm Mr. Murder

Mr. Murder